Algorithm-Driven Hiring Tools: Innovative Recruitment or Expedited Disability Discrimination? by Lydia X. Z. Brown, Ridhi Shetty and Michelle Richardson, presents us with a compelling report on the consequences AI based assessments have on employment of the disabled. Many of us revel in all the latest advancements in technology. We think the more tech, the better. Brown, et al., however, immediately set about clearing up any misperceptions we may have had about the neutrality and fairness of artificial intelligence-based hiring tests. We are treated to an informative and eye-opening breakdown of all the different types of tools and tests currently being used for hiring. Although it is not expressly noted by Brown, who is autistic and an expert on disability rights and algorithmic fairness, it is clear neurodivergent employment candidates have a high potential for being discriminated against via these tests. The authors also make certain to share with us that many employers do not realize how biased these tests can be. Hence, Brown, et al., spend a great deal of time pointing out the numerous ways an employer could be held liable for discrimination under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)1. As such, this report proves to be a valuable resource for self-advocates and employers alike. It is important to note that it was prepared by the Center for Democracy, an advocacy group who focuses on equity in civic technology and digital privacy/data among other things.

More than anything else, this paper is an exercise in both empowerment and how to be an anti-ableist in the hiring process. It educates us on the use of personality tests, face and voice recognition and resume screening for patterns. The authors remind us that algorithms are created by people and people have bias. Hence there are biased algorithms. We are provided with shocking statistics such as,

“76% of companies with more than 100 employees use personality tests.”

“An estimated 33% of businesses use some form of artificial intelligence in hiring and other HR practices.”

“The employment rate for people with disabilities is about 37%, compared to 79% for people without disabilities.”

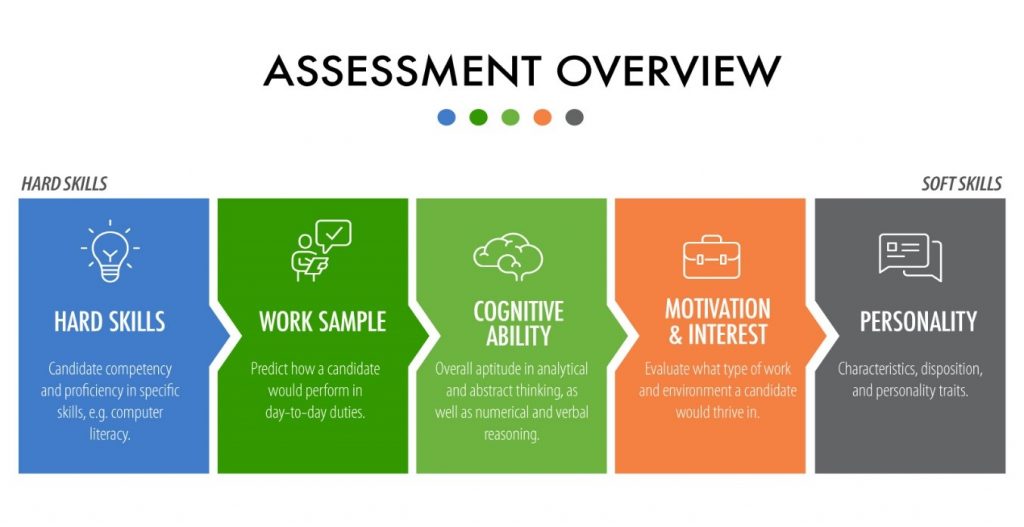

The authors inform us that many software developers market hiring assessment software to employers that not only measure a potential employee’s proficiency at the job, but other skills like cognitive ability (abstract thinking), motivation and personality. It seems that developers don’t factor in ADA regulations, such as using criteria that have the effect of discrimination, into their software and employers don’t ask them to. As Brown, et al educate us, this is problematic because some skills might not even be relevant to the job being applied for and knock a person with autism or even depression out of the running. We learn that candidates are ultimately chosen, not by a human, but by a machine. Machines ignore nuances and context and lack empathy. Just as the articles we read in class helped enlighten us on what unconscious bias and inclusion are, Brown, et al., are resolute in persuading us that the abilities many of us take for granted, like good eye contact, could make us blind to how people with disabilities (folks with autism in this case) are forced to maneuver the employment landscape.

Figure 1 Screen capture from info.recruitics.com

The authors offer us insight into how the intersection of people’s disability, race and socioeconomic status leads to hiring discrimination. This is something our class might want to further explore. What if a job seeker is applying for a low-wage warehouse job or looking to flip burgers? Why should a personality test matter? What if you are not white or male? Will the test indicate that you won’t thrive socially in a work environment dissimilar to your own social network because the software was developed by white men?

As mentioned earlier, Brown, an autistic person who also possesses intersecting identities, is a champion for equity in hiring. They appeared in HBO Max’s documentary2 “Persona: The Dark Truth Behind Personality Tests” where they elaborated on the devastating effects of digital hiring assessments on neurodivergent people and other marginalized groups. Not only will disabled readers see that Brown, is like them and advocating for them, but the authors hope to appeal to our ability to empathize with people unlike ourselves. Brown, et al., also “walk the walk” by providing a plain english version of their report and offering solutions (like using disabled software developers) based on Civil Rights Principles for Hiring Assessment Technologies3

Some may say the report itself is biased. But is it bias if you’re telling the truth?

Footnotes

Source:

- 42 U.S.C. § 12112(b)(6) (2018); 29C.F.R. § 1630.10(a) (2019). Three other ADA provisions similarly prohibit disparate impact of people with disabilities. These prohibit (1) limiting, segregating, and classifying an applicant or employee in a way that adversely affects their opportunities or status because of their disability; (2) contractual or other relationships that have the effect of disability discrimination (a simple agency theory of liability); and (3) utilizing standards, criteria, or methods of administration that have the effect of disability discrimination. 42 U.S.C. § 12112(b)(1)-(3) (2018), 29 C.F.R. § 1630.5-.7(2019).

- HBO Max, Persona the Dark Truth Behind Personality Tests Persona | Official Trailer | HBO Max – YouTube

- See Leadership Conference on Civil & Human Rights, Civil Rights Principles for Hiring Assessment Technologies (Jul. 2020), https://civilrights.org/resource/civil-rights-principles-for-hiring-assessment-technologies/.